The Insidious Spread of Opioids in Rural Appalachia

By Amanda Drws

Kudzu /ˈkʊd.zuː/

A fast-growing flowering vine native to Japan, capable of growing up to 60 feet in a season. Originally introduced in the 1930s as cattle fodder and a solution to erosion created during the time of the Dust Bowl.

Unfortunately, the qualities that made kudzu a potential solution were also what made it a successful invasive species. It is now found in 32 states and millions are spent in efforts to control it every year. [2.]

Stranglehold

When opioids were first introduced by Purdue Pharma in the late 1990s, they were marketed as a safe, non-addictive solution to chronic pain. The drug took root and spread quickly. Cancer patients, people with traumatic injuries, and those out of work due to chronic pain could now find relief without the fear or side effects of previous pain control options. Purdue leaned heavily on the idea of getting people back to their normal lives, quickly and easily. Opioids were hailed as a miracle solution.

Long after Oxycontin was released in the 90s, documentation from Purdue Pharma was released, showing that Purdue executives were aware of the negative side effects and potential for addiction. In the 50s and 60s, Arthur Sackler pioneered new marketing tactics for addictive drugs such as Valium. They were so effective that a generation of mothers suffering from valium addiction is widely forgotten [3.]. Under his son, Richard Sackler, and soon-to-be CEO Michael Friedman, those tactics were honed. Purdue hosted doctors for weekend meetings and dinners while burying initial trials that showed 82% of osteoarthritis patients had an adverse event as a result of their opioid treatment. Documentation showed that Purdue Pharma executives were not only aware of the potential for addiction, they set out to specifically dismiss those concerns. [4.]

In 2019, the Washington Post won a protracted legal battle and gained access to the Drug Enforcement Administration’s reporting system. ARCOS (Automation of Reports and Consolidated Order System) tracks controlled substances as they move from manufacturing through distribution via hospitals, pharmacies, practitioners, and teaching institutions. The Post made this data from 2006-2019 publicly available to anyone looking to better understand how opioids impacted their community. [13.]

The Washington Post has reported the movement of opioids primarily in number of pills, and focused on tablet formulations as they were most often diverted into illegal use. However, Purdue Pharma created OxyContin and other opioids in a variety of strengths to better expand their marketing capabilities. In order to standardize the amount of opioids moving through counties, here they are presented in Milligrams of Morphine Equivalent, or MME, a commonly used measure in medicine and pharmacology. Opioid rates peaked in 2010 - 2011, then began decreasing when national guidelines were released, with stricter prescribing rates to combat rising overdoses and death. [7.]

By the early 2000s, OxyContin and its variants were one of the most commonly prescribed drugs, and addiction and overdose rates soared. OxyContin and its related variants had the United States in a stranglehold.

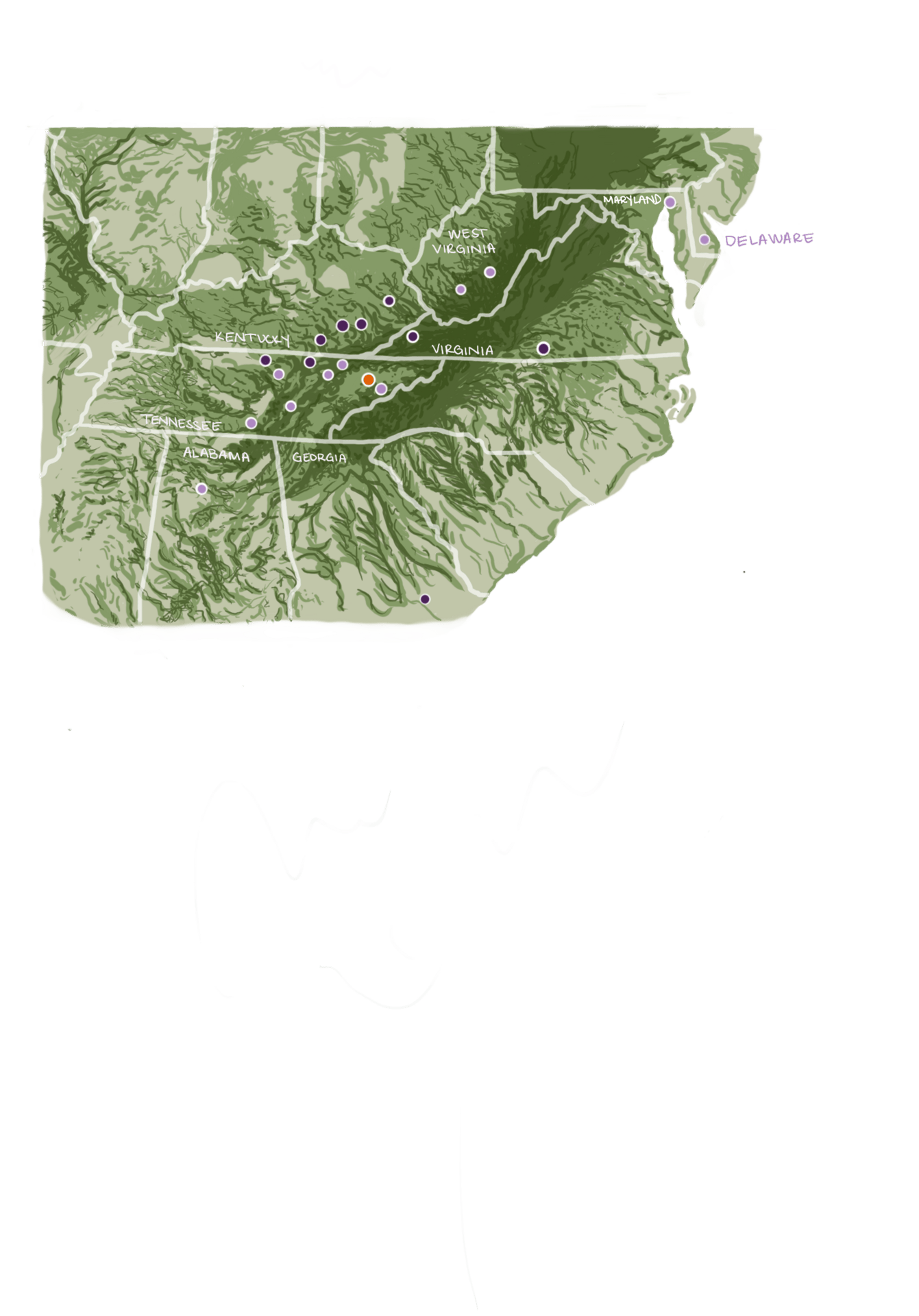

Looking at the country as a whole can hide counties in crisis

Looking at the county as a whole, it’s clear that some areas of the United States were more impacted than others. However, it’s easy to misjudge the extreme differences in volume that some counties were experiencing at the height of opioid overprescribing.

In 2011, Hamblen County had a per capita opioid use rate of nearly 7 times the national average and more than twice as high as the 90th percent. It has the dubious honor to be home to one of the top 50 opioid prescribers in the country, and top 20 prescribers in small communities. Dr. Abdelrahman Mohamed ran a described “drive through pill-mill” where he saw 40-60 patients a day for no more than a few minutes at a time, handing out pre-written pain prescriptions [10.]. Somehow, it took years for officials to notice, although it was logged in call notes by Purdue Pharma. [9.]

With Hamblen County surrounded by more rural areas and within driving distance of 3 other states, it’s very possible that the pills prescribed made their way deeper into the Appalachian mountains and disappeared from there. While these opioids may have entered the illegal drug trade, it is also true that Tennessee, and Hamblen County specifically, suffered extremely high rates of overdose and deaths due to opioid use. [16.]

It isn’t clear if Dr. Mohamed opened his practice in Morristown in 2006 with the intention of running a pill mill and defrauding Medicare and Medicaid. Lawsuits name timelines from 2010-2016, but certainly by the time Hamblen Neuroscience Center opened, opioids were on the rise. His work history is not publicly available between his fellowship at Wake Forest University in North Carolina in 1998 and his practice opening 8 years later. [5.]

Whether Dr. Mohamed came to Hamblen with a strategy in place, or was later influenced to make more money at the cost of his oaths as a doctor, specific conditions in Hamblen County allowed him the opportunity to harm a community. Only 21 counties had rates above 1,500 MME per person in 2011—something in these counties and not others made them especially easy targets and especially lucrative. Finding commonalities can give better insight into what makes a county susceptible to predatory doctors and pharmaceutical marketing tactics.

Historically Oppressed, Historically Resillient

Nearly all of the counties in the upper ~1% of opioid use fall in the Appalachian region, along the western side of the mountain range. This area of the United States was much more cut off from the rest of the European settlers and traders during the 17 and 1800s, and didn’t receive the same benefits from shipping and advancements. They grew mistrustful of the government and people on both sides of the Civil War, who fought, destroyed farms and livestock, and left. Dialects unique to Appalachia evolved, further reinforcing isolationist tendencies in the region. [12.]

Coal mining and logging in the Appalachian region took off in the 1900s, and rapidly became the main industry. Much of the culture at this time revolved around company-owned towns, and soon, the effects of unsustainable methods of industry. Strip mining and mountaintop removal mining were widely practiced in the second half of the 1900’s, leading to massive environmental and public health damage.

Coal mining and logging in the Appalachian region took off in the 1900s, and rapidly became the main industries. Much of the culture at this time revolved around company-owned towns, and soon, culture also included the effects of unsustainable methods of industry. Strip mining and mountaintop removal mining were widely practiced in the second half of the 1900s, leading to massive environmental and public health damage. A great deal of the music, art, poetry, and writing from the region has revolved around self-sufficiency, mistrust of outsiders, and grief over the harm being caused to the land and people.

Mountaintop removal mining is especially common in areas of Appalachia where steep hills and valleys make it the most accessible means of mining coal. A common illness among miners regardless of method is Black Lung disease, caused by inhaling so much coal dust. However, mountaintop removal mining sends more particles and contaminants into the air and water than other methods. This leads to much higher rates of lung cancer, heart disease, COPD, and birth defects, impacting the entire community, not just the miners. [1.]

Approximately 10% of all counties in the United States rely on mining as their main economic industry, but in the top 1% of opioid use counties, mining accounts for 24% of primary industry. This does not include counties that have mining as part of their economy, but fall under “Nonspecialized.”

Residents in these counties have very few options besides continuing to work in the industry making them sick. As use of coal decreases, income from mining industries also falls. When these companies move locations, other industries are unwilling to move into an area that is deforested, contaminated, and populated by an unhealthy community.

25.

soil rich with lime

grass beyond green

turning toward blue

hills of plenty

all but gone

bent under the weight

all human greed

we speak then

tell of a god of miracles

who moves mountains

yet manmade steel

ravishes this earth

all for coal

deep and black

a destiny of burning heat

covering flesh in ash

bell hooks

" When places are scarred, it is easy to look away from them while extracting what is needed from them. Simply put, the stories we tell about a place matter. [...] But this is no eulogy. We needed no elegy."

Meredith McCarroll

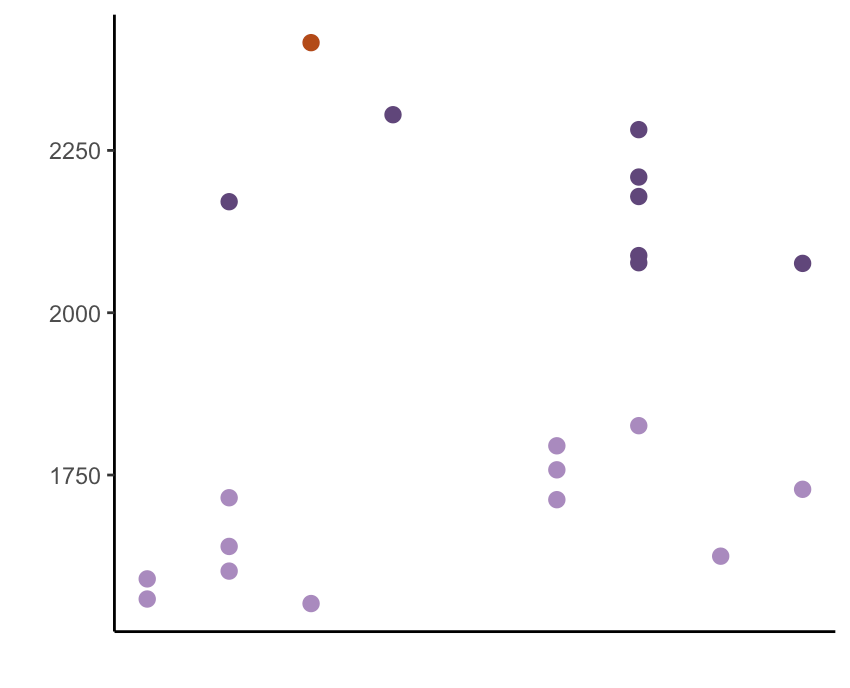

Levels of Rurality

Opioid MME

4.

1.

2.

3.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

Rurality and the Cost of Access

Levels of rurality

1. Metro - Counties in metro areas of 1 million population or more

2. Metro - Counties in metro areas of 250,000 to 1 million population

3. Metro - Counties in metro areas of fewer than 250,000 population

4. Nonmetro - Urban population of 20,000 or more, adjacent to a metro area

5. Nonmetro - Urban population of 20,000 or more, not adjacent to a metro area

6. Nonmetro - Urban population of 2,500 to 19,999, adjacent to a metro area

7. Nonmetro - Urban population of 2,500 to 19,999, not adjacent to a metro area

8. Nonmetro - Completely rural or less than 2,500 urban population, adjacent to a metro area

9. Nonmetro - Completely rural or less than 2,500 urban population, not adjacent to a metro area

More than half of the top 1% of counties are found in non-metro and rural locations, and these counties trend towards heavier use than the counties in metro areas. Hamblen County is considered a level 3 metro county, but as a manufacturing center, it pulls its workforce from the 7 surrounding counties. It is likely that these workers also get healthcare in Hamblen and account for some of the opioid prescriptions.

One of the significant challenges that rural counties face is access to healthcare. Rural counties often have limited healthcare services, and people living in these regions may be unwilling or unable to travel the distances required for routine care. Specialists are often even further away.

Medicaid coverage data shows that emergency room care is utilized at a rate 10% higher in rural adults vs urban adults, indicating that this population does not have a regular doctor or is in a medical emergency due to postponing or opting out of regular care. People who utilize the emergency room for their health needs instead of going to a primary care doctor are not going to be able to see physical therapists, orthopedic specialists, or other specialty care due to distance, time, or financial constraints. [8.]

At the intersection of inaccessible healthcare and economies dominated by harmful industries, we find Appalachia. Industry constraints limit the population’s ability to change jobs and increase the need for healthcare, while location and time constraints push residents towards solutions in a single visit. This creates fertile ground for opioids to take root.

County health is a complex web

Ranking County Health

Opioid use disorder has been reported as strongly correlated to low income and low education status. However, this is a sweeping generalization, is not the root cause, and fails to account for the range of household incomes, economic types, and cost of living that can vary across the United States.

The counties in the top 1% of opioid use are outliers, but only in that measurement. There are trends when it comes to health rankings, but no single measurement that can be conclusively linked to opioid use on the county level. These counties are under different combinations of stressors and pressures that primed them for opioid use.

How to read the following visual:

The counties with the top 1% of per capita opioid use were ranked by percentile against all counties in the United States. The colors correspond to previous visuals, with Hamblen County in orange. Putting these variables into percentiles allows for the comparison of different units or different scales.

The biggest expense that contributes to cost-of-living estimates in a region is housing prices. In some cases, median household income does not rise with high housing prices. This causes financial strain, especially in areas that do not have as many opportunities for job changes or upward mobility.

When considering the strain that might lead county residents to opioid use and opioid use disorder, it’s difficult to draw direct correlations. Some are measurable, such as the pressure of high housing costs, which can be mitigated by equally high household income. Some are harder to quantify, such as the additional pressure that single parents experience that may be buffered by strong family and community support when a child or parent is ill. Each of these aspects push and pull on county resources, and counties that have face similar problems due to being under-resourced may arrive there in very different ways.

Unemployment rates are a good signal for an area’s opportunity for job changes. An area that has a high rate of unemployment will have fewer options for people to change jobs as there are more job seekers than positions available. For residents in an area with high unemployment, they may be unwilling or unable to leave a position without taking a significant hit to their income.

This can lead to high rates of poverty, increasing the likelihood that residents will keep even low-paying jobs or physically demanding and harmful jobs.

Education level is also a factor when it comes to job changes or upward mobility. In areas with predominantly blue-collar jobs such as manufacturing or mining, bachelor’s degrees or higher may not be required to have a reliable and comfortable income. However, if these job providers close or move, or if injury prevents work, lack of higher education can limit residents’ options for income. This will also increase the likelihood that residents stay in jobs that are physically detrimental to their health.

The average American reads at a 7th-8th grade level. High rates of illiteracy, defined as the inability to read above a basic level or complete tasks such as following written instructions, can further limit an individual’s ability to gain financial security.

Many things can go into median household income, but one of the most important factors is the number of working adults in the house. Households with single parents have only one income, and this can cause additional stressors when the parent or child is ill, especially if they do not have family or a social buffer and have to take time off work. The ability to work around school hours or take time off for childhood illnesses can keep single parents working in detrimental jobs. This can also lead to young adults entering the workforce earlier to support their family, reducing their options for pursuing higher education.

Teen birth rates can also be a source of financial strain, as additional expenses are incurred before savings and careers are established.

Teen births are correlated with low birth weight, which can cause future health issues. Low birth weight can also be a sign of poor maternal health or underlying chronic conditions.

Other signs of chronic health conditions include diabetes rates and rates of obesity. These are only signals of chronic health issues in a community, but areas with high rates of these health issues are correlated with overall rates of poor health. Areas with high rates of poor health also report high rates of inactivity, which can lead to poor mental health. All of these factors can limit income opportunities and can require healthcare that residents simply do not have access to.

None of these factors in isolation predict high rates of opioid use, but when viewed in whole, it becomes easier to understand the pressures and limited options that lead to a community susceptible to opioid marketing. Opioids were originally highly recommended for chronic low back pain, a common workplace injury. Physical therapy and other pain management modalities are now known to be the standard of care, but residents may not have access to those healthcare facilities. They also are not short-term or immediate solutions, and residents may not have the ability to take time off work to pursue them, especially in rural areas.

With doctors encouraged to prescribe opioids as a non-addictive solution to common pain complaints, all other pain management options an hour away and requiring weeks or months for effect, no alternate job options, and little to no financial or social buffer, it quickly becomes clear that for residents in these counties, it’s not a matter of picking from bad options. Taking prescribed opioids was their only option.

When all measures are viewed together at the county level, it becomes easier to see which areas are causing the community the most strain and may be contributing to their high rate of opioid use.

Counties Spread Thin

The Region as a Whole

The downstream impact of struggling counties cannot be understated.

Approximately 42% of people who misused prescription painkillers in 2020 got a prescription from a licensed doctor for a legitimate pain complaint. An additional 47% of people who misused opioid painkillers got them from a friend or family member. When asked why, nearly 65% of respondents to a SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) survey reported that they used opioids that were not prescribed to them or at a higher level than prescribed in order to relieve pain. The NIH (National Institutes of Health) defines this as “nonmedical” use even if the person could have received a prescription for the same complaint. [14.]

A separate NIH study reported that nearly 80% of heroin users who started use in the 2000s used opioid prescriptions before turning to heroin [11.]. As opioids are an expensive, controlled substance, people with opioid use disorder may start using heroin as a cheaper and more accessible alternative. However, illicit drug manufacturers have begun adding fentanyl to the drugs they sell. Fentanyl can dramatically increase the potency of these drugs, but it is also extremely easy to add lethal doses. Studies by the CDC indicate that fentanyl is the leading cause of opioid-related overdose deaths, which continue to rise. [6.]

When viewed as a whole, Appalachia is struggling. Longterm oppression and profits over people have put this region under strain. Addiction medicine clinics and treatment centers can only do so much when people return right back to the environment that caused them to turn to opioids in the first place.

Valium in the 60s and 70s. Opioids in the 2000s and 2010s. The next serious pharmaceutical addictive substance has not been identified, but the country as a whole is still struggling with downstream impacts of opioids leading to heroin and fentanyl use. Rates of overdose and death continue to be high, and the non-lethal effects that this has on communities is hard to define.

If the true goal is to address rates of addiction and not to punish people who use drugs, criminalizing drug use is not the answer. Even opening treatment centers and offering harm reduction options can only go so far. Only by understanding what led people to drug use—and likely, their first drug was prescription opioids—and addressing it at the community level can we treat the root cause and not just put a bandaid over the problem.

In all cases, it is very rarely an either/or solution. Treatment from doctors and addiction medicine specialists are still needed for people who are already coping with use disorders. However, waiting for substance use disorder to occur and then taking action is reactive. Removing barriers to care and providing options that each community specifically needs could reduce the need for treatment centers, massively cut healthcare costs, and save more lives.

The first step in truly rooting out addiction at its source is understanding what most restricts a community’s options, and relieving that pressure.

Under Pressure